Recovering the Scale, Rotation and Translation Matrices from the Model Matrix

$\newcommand{\mvec}[1]{\mathbf{#1}}\newcommand{\gvec}[1]{\boldsymbol{#1}}\definecolor{colr}{RGB}{220,0,0}\definecolor{colg}{RGB}{0,220,0}\definecolor{colb}{RGB}{0,0,220}$BEGIN EDIT

I will add a small edit before we begin: We write our matrices in Column-major order. This for instance means that we write our translation matrix as \begin{equation*} T= \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 & 0 & t_x \\ 0 & 1 & 0 & t_y \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & t_z \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix}, \end{equation*} To translate a vector, we write $T * \mvec{v}$, where $\mvec{v}$ is a column vector. For further info, please read this article

END EDIT

In many rendering engines, the model matrix is used to translate, scale and rotate objects in the world. Put more formally, it is a matrix that transforms from object space to world space, and it is for this reason also called the ObjectToWorld matrix in some engines. As a small exercise, I will in this post show how to recover the separate translation, scale, and rotation matrices from the model matrix. I occasionally find it to be useful to do so, when I am debugging some graphics code, and need to sanity check and verify that my model matrix contains values that are sensible.

The model matrix is the matrix product of a scale matrix $S$ \begin{equation*} S= \begin{bmatrix} s_x & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & s_y & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & s_z & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix}, \end{equation*} and a rotation matrix $R$ \begin{equation*} R = \begin{bmatrix} R_{x,x} & R_{y,x} & R_{z,x} & 0 \\ R_{x,y} & R_{y,y} & R_{z,y} & 0 \\ R_{x,z} & R_{y,z} & R_{z,z} & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix}, \end{equation*} and a translation matrix $T$ \begin{equation*} T= \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 & 0 & t_x \\ 0 & 1 & 0 & t_y \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & t_z \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix}, \end{equation*} A common order, is that first the scale matrix is applied, then the rotation matrix, and finally the translation matrix. This means the model matrix $M$ is \begin{equation*} M = T * R * S \end{equation*} We will begin by rewriting $M$ in a more useful form. First of all, we have that \begin{equation*} T * R = \begin{bmatrix} R_{x,x} & R_{y,x} & R_{z,x} & t_x \\ R_{x,y} & R_{y,y} & R_{z,y} & t_y \\ R_{x,z} & R_{y,z} & R_{z,z} & t_z \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix} \end{equation*} So $M$ can be written as \begin{equation*} M = T * R * S = \begin{bmatrix} R_{x,x} * s_x & R_{y,x} * s_y & R_{z,x} * s_z & t_x \\ R_{x,y} * s_x & R_{y,y} * s_y & R_{z,y} * s_z & t_y \\ R_{x,z} * s_x & R_{y,z} * s_y & R_{z,z} * s_z & t_z \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix} \end{equation*} From this form of $M$, it is not difficult to recover the three matrices $T$, $R$ and $S$. However, before that, I will first explain some things about the rotation matrix $R$. The rotation matrix is written as \begin{equation*} R = \begin{bmatrix} R_{x,x} & R_{y,x} & R_{z,x} & 0 \\ R_{x,y} & R_{y,y} & R_{z,y} & 0 \\ R_{x,z} & R_{y,z} & R_{z,z} & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix}, \end{equation*} Observe that only the block of values from row 1 to row 3, and column 1 to 3(using one-based indexing) contains useful values. In this block, we have three column vectors that decide the new values of the xyz-axes, if we apply this rotation matrix. As an example, consider the rotation matrix \begin{equation*} R = \begin{bmatrix} -0.853553 & -0.146447 & -0.500002 & 0 \\ 0.5 & -0.5 & -0.707103 & 0 \\ -0.146447 & -0.853553 & 0.500002 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix}, \end{equation*} Essentially, when an object is rotated by this rotation matrix, then the default $\color{colr}{x}$-axis $\color{colr}{[1,0,0]^T}$ is rotated to become $\color{colr}{[R_{x,x}, R_{x,y}, R_{x,z}]^T = [-0.853553, 0.5, -0.146447]^T}$, and the $\color{colg}{y}$-axis is rotated to become $\color{colg}{[R_{y,x}, R_{y,y}, R_{y,z}]^T}$, and finally, the $\color{colb}{z}$-axis is rotated to become $\color{colb}{[R_{z,x}, R_{z,y}, R_{z,z}]^T}$. The below image shows the original and rotated axes resulting for this matrix $R$.

Furthermore, when the $xyz$-axes are rotated, also the object is rotated to align with these new axis. The below animation illustrates this, when rotating a cube mesh

The rotation shown in the animation, is the rotation specified by the rotation matrix $R$. So rotations are simply described by specifying new values for the $xyz$-axes.

The original axes $\color{colr}{[1,0,0]^T}$, $\color{colg}{[0,1,0]^T}$, $\color{colb}{[0,0,1]^T}$ specifies an orthonormal basis. This means that all axis vectors must be normalized(have magnitude equal to one), and they must be orthogonal to each other, meaning the angles between them are perpendicular angles. It is simple to verify that they form an orthonormal basis. They are clearly normalized, since \begin{equation*} [1,0,0]^T \cdot [1,0,0]^T = 1 \\ [0,1,0]^T \cdot [0,1,0]^T = 1 \\ [0,0,1]^T \cdot [0,0,1]^T = 1 \end{equation*} Two vectors are orthogonal to each other, if their dot product is zero. And these are vectors are clearly orthogonal to each other: \begin{equation*} [1,0,0]^T \cdot [0,1,0]^T = 0\\ [1,0,0]^T \cdot [0,0,1]^T = 0\\ [0,1,0]^T \cdot [1,0,0]^T = 0\\ [0,1,0]^T \cdot [0,0,1]^T = 0\\ [0,0,1]^T \cdot [1,0,0]^T = 0\\ [0,0,1]^T \cdot [0,1,0]^T = 0 \end{equation*} Since the original coordinate axes form an orthonormal basis, the three axis vectors specified by a rotation matrix must also form an orthonormal basis. The previous rotation matrix \begin{equation*} R = \begin{bmatrix} -0.853553 & -0.146447 & -0.500002 & 0 \\ 0.5 & -0.5 & -0.707103 & 0 \\ -0.146447 & -0.853553 & 0.500002 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix}, \end{equation*} clearly specifies an orthonormal basis, and we leave it as an exercise to the reader to verify this fact.

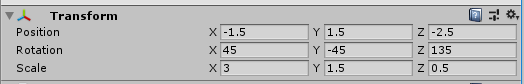

Having embarked on a small detour in order to explain the interpretation of the rotation matrix, we now return to the original subject: recovering the translation, rotation and scale matrices from the model matrix. We found that $M$ can be written as \begin{equation*} M = T * R * S = \begin{bmatrix} R_{x,x} * s_x & R_{y,x} * s_y & R_{z,x} * s_z & t_x \\ R_{x,y} * s_x & R_{y,y} * s_y & R_{z,y} * s_z & t_y \\ R_{x,z} * s_x & R_{y,z} * s_y & R_{z,z} * s_z & t_z \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix} \end{equation*} Let us now take a model matrix from some rendering engine. In this case, I recovered this model matrix from the rendering engine of Unity using RenderDoc: \begin{equation*} M_2 = \begin{bmatrix} -2.56066 & -0.21967& -0.25 & -1.50 \\ 1.50 & -0.75& -0.35355 & 1.50\\ -0.43934 & -1.28033 & 0.25 & -2.50 \\ 0.00 & 0.00 & 0.00 & 1.00 \end{bmatrix} \end{equation*} Since the fourth row is $[0, 0, 0, 1]$, we can see that this is a column-major order matrix, so all our derived formulas will work for this matrix. If it is a row-major order matrix, it can just be transposed, before we recover the three matrices. Comparing $M_2$ with $M$, we see that we can recover the translation values from the fourth column. So $t_x = -1.50$, $t_y, = 1.50$ and $t_z = -2.50$. Also, as we just stated, the columns of the rotation matrix must form an orthonormal basis, which means that the vectors in these columns must have magnitude one. This means that $[R_{x,x}, R_{x,y}, R_{x,z}]^T$ must have magnitude 1, and therefore we can recover $s_x$ by calculating the magnitude of $[-2.56066, 1.50, -0.43934]^T$, and same reasoning applies for $s_y$ and $s_z$: \begin{align*} s_x &= ||[-2.56066 ,1.50, -0.43934]^T|| = 3\\ s_y &= ||[-0.21967, -0.75, -1.28033]^T|| = 1.5\\ s_z &= ||[-0.25, -0.35355, 0.25]^T|| = 0.499998 \end{align*} Finally, if we normalize these vectors, instead of computing their magnitudes, we recover the rotation matrix. Normalizing $[-2.56066 ,1.50, -0.43934]^T$ yields $[-0.853553, 0.5, -0.146447]^T = [R_{x,x}, R_{x,y}, R_{x,z}]^T$, and we repeat this for the remaining vectors, and this gives us the rotation matrix \begin{equation*} R = \begin{bmatrix} -0.853553 & -0.146447 & -0.500002 & 0 \\ 0.5 & -0.5 & -0.707103 & 0 \\ -0.146447 & -0.853553 & 0.500002 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix}, \end{equation*} To conclude, we have recovered our three matrices: \begin{equation*} S = \begin{bmatrix} 3 & 0& 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 1.5 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0.499998 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix}, \end{equation*} and \begin{equation*} R = \begin{bmatrix} -0.853553 & -0.146447 & -0.500002 & 0 \\ 0.5 & -0.5 & -0.707103 & 0 \\ -0.146447 & -0.853553 & 0.500002 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix}, \end{equation*} and \begin{equation*} T = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0& 0 & -1.50 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 & 1.50 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & -2.50 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix}, \end{equation*} The parameters I used to create this model matrix in Unity can be seen below:

So we were able to recover all parameters that we specified in Unity, which shows that our little endeavor was a success. Note that we did not however recover the original euler angles of the rotation, but I rarely find it useful to recover these values, since having the axis vectors of the rotation matrix is enough for visualizing the rotation. The parameters specified in Unity describe a rotation matrix that first does a $z$-axis rotation by $135$, then an $x$-axis rotation by $45$ degrees, and then $y$-axis rotation by $-45$ degrees(this rotation order is documented by the Unity Documentation). Each of these three rotations becomes a separate rotation matrix, and by multiplying them together we obtain the final rotation matrix, which can be calculated here in Wolfram Alpha. Comparing the value calculated by Wolfram Alpha to our $R$ matrix, we can see that we indeed recovered the correct rotation matrix.

Finally, note that the specified value for $s_z$ was 0.5, but we recovered $0.499998$. This shows that recovering the values in this manner results in a loss of floating-point precision, which is not good when good precision is necessary, such as when rendering large worlds. For this reason, I mostly use this approach when I want to do a quick-and-dirty sanity check of my model matrix when debugging graphics code, but not when I want to recover values with good precision.